Key takeaways

- This interview features Heather Forkey, MD, Associate Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, and Moira Szilagyi, MD, PhD, general academic pediatrician at the University of California, Los Angeles.

- The Covid-19 pandemic placed even greater distress on vulnerable populations, including children in foster care, juvenile justice, poverty, immigrant families, and those with medical complexity or disabilities.

- As children’s first responders, parents and caregivers need to feel safe, believe they can do their job, and have the ability to regulate themselves in order to co-regulate their children. Children need both “roots and wings,” grounded in family history and connection as well as hope fostered through gratitude and caring for others.

- Healthy child development depends on early attachment and caregiving, as parents and caregivers help regulate a child’s stress response and support higher brain functions. Children mirror adult emotions but lack management skills, so caregivers can build resilience by modeling and reflecting on how they handle stress.

This interview summary was created with the assistance of artificial intelligence (AI) and reviewed by the HOPE National Resource Center staff before publication. No other parts of the blog post were generated by AI. Found an error? Let us know.

Support parents and caregivers to create positive childhood experiences:

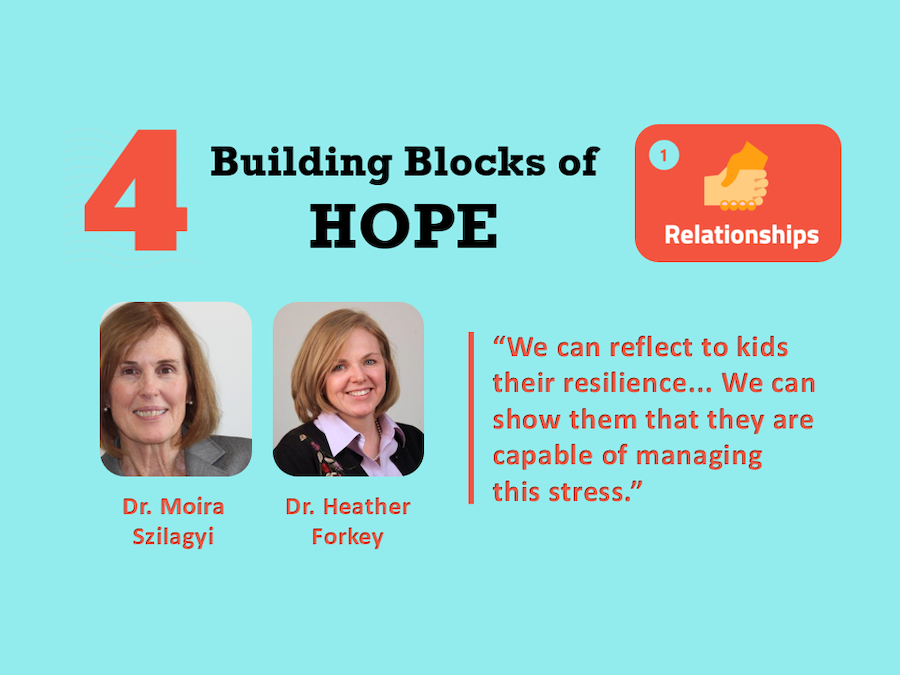

All children need positive childhood experiences (PCEs). The HOPE National Resource Center believes that every child in each community should have access to the key types of PCEs that we call the Four Building Blocks of HOPE: safe and supportive relationships that are critical for children to develop into healthy, resilient adults; safe, stable, equitable environments to live, learn, and play; opportunities for social and civic engagement to develop a sense of belonging; and opportunities for emotional growth. Being in nurturing, supportive relationships are critical for children to develop into healthy, resilient adults. Safe and supportive relationships are the first Building Block, and an important PCE is that children have parents/caregivers who are responsive and interact warmly with them. This blog features an interview with Heather Forkey, MD and Moira Szilagyi, MD, PhD who discusses vulnerable children, the Building Block of Relationships, resilience and child development, as well as supporting children and families during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Dr. Forkey is an Associate Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Massachusetts Medical school and a pediatrician at UMass Memorial Medical Center. There, she runs FaCES (Foster Children Evaluation Service) and heads the Child Protection Program. Dr. Szilagyi is a general academic pediatrician at UCLA, interim division chief of general pediatrics, and section chief of developmental behavioral pediatrics. She provides clinical care in one of Los Angeles County’s medical hubs for children involved with child welfare.

How did you became interested in Healthy Outcomes from Positive Experiences (HOPE) and positive childhood experiences (PCEs)?

Dr. Szilagyi: I’m an immigrant, daughter of a bricklayer. I grew up in a low-income neighborhood, in a wonderful family. My brother and I were very fortunate in having amazing parents who sent us to good schools, and I had mentors everywhere along the way. So many of our peers did not have those opportunities. When I finally decided to go to medical school, I was in my late 20s, and I had my first child in medical school. It got me thinking—how do you know, with this little life you’ve been entrusted with, that you can give them the right things? How did my brother and I succeed and move beyond our neighborhood? [I became] very interested in child development.

Then I discovered the resilience research literature. Decades of resilience research teaches us that resilience develops over time; it is woven into human evolution and human development. But it is dependent on the earliest relationships children have, because all the other resilience characteristics develop in the context of the primary relationships. That’s why I love Anne Masten’s term, “ordinary magic.” Resilience is not magic—it’s the outcome of exposure to typical nurturance and experiences.

We often have very little control over the bad things [like Adverse Childhood Experiences]. What we do have control over, especially for children, is the support of the caregiving relationship. Threads of resilience are embedded in that relationship. -Heather Forkey, MD

Dr. Forkey: Dr. Szilagyi introduced me to the work of Anne Masten, the brilliant resilience researcher who identified resilience as “ordinary magic” and laid out the attributes of resilience that we can grow in kids through caregiving relationships. It’s in that trajectory you begin to see what creates resilience. You have to understand resilience to then appreciate what is being pathologized to cause the problem. [Trauma] has its impact through a lack of buffering relationships.

As the ACEs idea has [popularized], people have become very focused on the bad things people experience. We often have very little control over the bad things. What we do have control over, especially for children, is the support of the caregiving relationship. Threads of resilience are embedded in that relationship.

Which children are particularly vulnerable at this time?

Dr. Szilagyi: With the pandemic, very vulnerable subpopulations are even more distressed than usual. This is not to say that people with more financial resources aren’t stressed. But I always worry about children involved with child welfare and foster care and juvenile justice. Children living in poverty. Immigrant children. Undocumented immigrants who are disconnected from services. Children with medical complexity. Children with significant disabilities. People who are suffering felt discrimination. And then there’s people with housing insecurity at a time when we’re all being asked to shelter-in-place. Right now, we have 15,000 kids in Los Angeles school districts who don’t have the technology to attend school in their homes, and 30,000 more who have limited internet access, so they have spotty attendance.

How can we support parents and create PCEs for their children?

Dr. Forkey: Parents are children’s first responders. What do they need, first and foremost? They need to feel safe. They need to feel they can do their job effectively. Many of them are in situations where they can’t feel safe, or have histories that make them feel unsafe, so it becomes very challenging to be the first responder to a child. I come back, again and again, to the three R’s for kids and parents. [Both] have to be reassured they’re safe, [they] have to have some routines, and [caregivers] have to be able to regulate [themselves] so they can co-regulate kids. You can’t give to your child what you don’t have yourself.

One of the first steps that we [ask]: who are the people that can help you? When you’re under distress, you can easily [think], I have no one. If you sit with someone and say, “What if something happened in the middle of the night. Who would you call? A neighbor downstairs? Your mother? And then, in the morning, who would you call?” People have more resources than they often think. Also, helping parents to know, it’s not the other children in the home. There’s needs to be other adults that they call.

For many of us in this Covid-19 period, we find ourselves spinning. You can’t think straight, you repeat yourself and do things over and over. That’s our prefrontal cortex not working. This is a really good learning time for those of us who haven’t been living under the same kinds of stressors as some families do, to gain a little more empathy and compassion for what it’s like to live [with those stressors] all the time.

Dr. Szilagyi: When things are all upside down, there’s a saying on the wall of my home: children need two things from us. The first is roots, the other is wings. It’s really important, when things feel so uncertain, to spend some time on the roots of your family. Spend time looking at pictures together, looking at those old videos that we all take and never have time to watch, telling [children] who Aunt Sue and Grandpa Frank are. Those things are grounding for children and give them a sense of security.

We know [Covid-19] is going to end. We just don’t know when. One of the ways we can manifest hope for each other is by remembering, at least once a day as a family, what are the things we have to be grateful for today? Families who are in a position to can look out for others during this time. Being focused on others is hard when you can’t be physically close to people, but you can still stay socially connected, leave something on somebody’s doorstep, or check in on an elderly person.

We can reflect to kids their resilience in each interaction. We can show them, by what we say and what we do, that they are capable of managing this [stress]. But they have to hear it. They have to see it from the caregiver’s perspective. -Heather Forkey, MD

How do these PCEs affect child development?

Dr. Forkey: We figure ourselves out because others reflect who we are back to us. The baby cries, mom picks up the baby and says, “Oh, you’re hungry,” and the baby learns, “This feeling, that was hunger.” But if mom is stressed, and she says, “Why do you keep bothering me? You’re so greedy!” The baby learns that feeling is greedy.

We can reflect to kids their resilience in each interaction. We can show them, by what we say and what we do, that they are capable of managing this [stress]. But they have to hear it. They have to see it from the caregiver’s perspective. We can also think about behaviors that seem problematic and recognize them for what they are. We talk about a cognitive triangle. When we see a behavior, it comes from the thoughts and feelings behind it. So when we see [problematic] behavior in a child, take a moment to step back and not say, “Stop that behavior,” but say, “What were you thinking about or feeling that led to that behavior?” Then they come away with another set of strategies for how to handle their own thoughts and feelings, which is what they’re learning to manage.

Dr. Szilagyi: As we’re helping children adjust during this time, we’re helping them build self-efficacy skills, and teaching them ways they can keep themselves and others safe. When we’re helping to manage their emotions, and to think about ways to be helpful and stay socially connected, we’re actually reinforcing those brain structures that lead to a resilient, competent human being. I realize it’s incredibly challenging for parents when they themselves are very anxious and trying to keep things positive for their kids. It’s ok for parents to say, “Sometimes I get a little overwhelmed, too,” and say to their child, “This is how I’m trying to manage my feelings during this time. But sometimes they might spill over.” Because you’re teaching children, this happens to everybody. We all have to learn to manage.

Can you elaborate a little more on how PCEs affect brain development?

Dr. Szilagyi: Healthy brain development is rooted in early attachment relationships and typical experiences. We grow our ability to manage stress. The alarm system in the brain develops early. Part of what a parent does, by comforting a child, is calm down the alarm system, enabling higher brain functions to come online and develop. This applies to your cognitive development, your executive function development, and mastering age appropriate developmental skills. All those are learned in the context of relationship. [Kids] are very attuned and attentive, especially to their caregivers. When they see an adult being stressed, it makes them feel stressed. They have all the same feelings we have. What they don’t have, depending on how old they are, is adult management skills. We can help children at this time by noticing how we’re feeling, by occasionally commenting on how we manage things. There are ways we can be reflective and use what we’re going through to help kids.

The interview was edited for brevity and clarity.