HOPE involves a change in mindset. For many of us, our professional training and inclinations lead us to discover risks, problems, and deficits. In this blog (the first from our new team member, Loren McCullough), we examine national data that points to severe problems with the food supply – as experienced by families. Hidden within the data, we also see evidence for hope. Family and community engagement have buffered some of these issues, creating safer environments for children living through the pandemic. These stopgap measures demonstrate resilience, but significant policy changes are needed to ensure every child a safe, stable, and equitable environment – which necessarily includes food security for themselves and their families.

As the long, hot summer of 2020 begins to fade, it’s becoming clearer than ever that the future of our country at large has been forever shifted by the coronavirus pandemic. For almost half a year, livelihoods and lifestyles have been warped by invisible hands, every system individually attempting to keep afloat.

The United States Census Bureau conducts a weekly household survey to illuminate the myriad effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Read more about this survey in the box below:

The 2020 Household Pulse Survey (HPS) was developed by the U.S. Census Bureau with the help of five partner agencies: the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the National Center for Health Statistics, the United States Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service, the National Center for Education Statistics, and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Data collection began in April 2020 and has stretched over twelve weeks. Using the incredible resource available through the Census database, the HPS was created “to help understand the social and economic impacts of COVID-19 on American households”[1] – an understanding which the Bureau claims is “critical to governmental and non-governmental response” to closures of schools, businesses, and stores. By asking a similar series of questions over twelve weeks, the HPS monitored health, employment, housing insufficiency, and educational changes.

Food supply and insufficiency:

Overall, it’s no secret that food service and distribution has been affected heavily in the wake of the pandemic: the leisure and hospitality sector has seen 20% increases in unemployment between February and May of this year. Along with economic impacts on American households, the Household Pulse Survey (HPS) highlights interesting trends in food sufficiency data. The survey includes data from a series of questions regarding eating habits, including how frequently the respondents’ household experienced insufficient, or “not enough,” food.

Over 60 million respondents from the HPS survey issued on Week 12 (July 16-21st) reported having children under the age of 18 living in the home with them. As part of food sufficiency questions, respondents were asked to describe the food eaten in their household over several time periods, whether they had enough food, enough food that was not the type preferred, sometimes enough food, or often not enough food. Prior to March 13, 2020, 87% of respondent households with children reported having enough food, whether or not it was the types preferred. When the same sample was asked what their household food access was like in mid-July, 82% of respondents with children reported enough food in the household. In observation of the slight decline, it is important to break these measures into component parts.

Let’s begin with types of food preferred – of the reasons for a change in household food access between March and July, while 50% of families report financial difficulty obtaining enough food, about 30% claimed that availability of food options in stores has been their larger problem. The pandemic and successive shutdowns have been difficult for small businesses in the food and hospitality sectors. Families who relied upon small community stores or restaurants may now be outsourcing from less familiar avenues. For some, this could be as easy as ordering in from the next town over or trying out a new recipe; for others, the picture is less rosy.

Lower income families have been hit hard in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. 60% of respondents with previously reported household income of under $25,000 have experienced a subsequent drop in income since March 2020. The pandemic, as it seems, has re-asserted disparities in food sufficiency that were present long before. The HPS responders reported that 63% of households who often struggled for food prior to COVID-19 continued to do so, as did 73% of families who “sometimes” had not enough food. Since the HPS investigates food sufficiency alone, these responses may represent a much larger food security problem that is reflected in national data on agriculture and food access. Seeing these hard numbers may depict a somber image of the U.S family’s food situation in the wake of coronavirus. However, with the HOPE lens, we can focus on the positive and identify the ways families may be demonstrating their resilience.

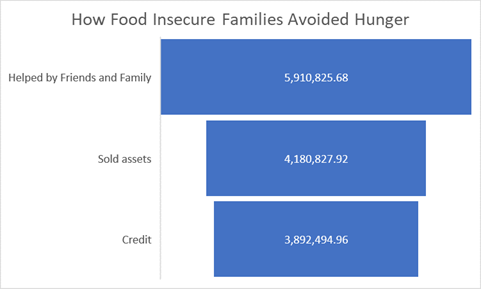

Of respondents with children in the home, one in two families reported their school-aged children having never gone without food due to financial insufficiency—this is despite 60% of the same sample reporting little to no confidence in being able to afford food in the coming month. Parents in the middle of a financially tumultuous period are doing everything they can to create stable and equitable home environments for their children, which includes providing food at any cost. Respondents reported selling assets, using savings, and other means of obtaining food at times when it would otherwise be inaccessible. The establishment of this HOPE building block lends to the children feeling safer at home during perilous days. Through all of this, however, parents in low-income households tend to report higher rates of anxiety and worry on the HPS.

Families and communities pulled together to address food insufficiency:

How, after all, are many families reporting getting enough food? The change in mindset that forms the core of HOPE helps us understand not only the problem – increasing food insufficiency – but the dramatic rise in community and family support that buffers its effects on children.

In their battery of questions, the HPS struck an important chord that illuminates the way HOPE across the nation is mitigating some of the lasting economic wounds inflicted by the pandemic. Of the means in which food has been obtained over the past week, 41% of families experiencing food insufficiency in the last 7 days reported receiving contributions from friends and family. In those who sometimes experience too little food, this number outweighs respondents who bought food on credit or sold assets by over 10%. (40% friends, compared to 29% sold assets, 27% bought on credit).

Communities have come together to fight against falling food access, and some are making a positive impact on their environment. The act of fostering engagement through community activities – from a local food bank to a neighborhood cookout – has become a method of spreading hope through our most common unifier.

Moving from emergency support networks to policies:

Food is more than sustenance. It is a cultural tool, a method of communion, and a primary point of interpersonal bonding. However, as much as human beings help one another with this need, the work of any one person, family, or neighborhood can only bandage part of a deep systemic wound. Resilient communities have stepped up to provide temporary support; however, without systemic solutions, the wound will continue to re-open. The harsh circumstances shown in the HPS illustrate an urgent need for a strong policy response to growing food insufficiency. Children and their families need basic supports during these unprecedented circumstances—their health and well-being hinge on such support.

Providers and advocates for child welfare are already pushing to see real change in these areas, pointing out specific programs such as SNAP that have the potential to present a longer-lasting safety net. The push for this change has begun. As policy moves focus on more equitable access to financial and nutritional resources for families in need, governments and organizations are given the chance to reach out and share with community neighbors in need.

By sharing our food, and thereby our HOPE, we open up avenues to others who have limited access. On the scale of friends and neighbors we come to each other’s aid in times of need, and with policy changes, we encourage systemic solutions and concrete support into the future.

Thank you to Stephanie Ettinger de Cuba, for her review of this post and for sharing resources with us. For more information on how to support research and advocacy surrounding food access for children, visit: https://childrenshealthwatch.org/

The photo used in the graphic above is from Tanaphong Toochinda on Unsplash

[1] Fields JF, Hunter-Childs J, Tersine A, Sisson J, Parker E, Velkoff V, Logan C, and Shin H. Design and Operation of the 2020 Household Pulse Survey, 2020. U.S. Census Bureau. Forthcoming.