Wouldn’t it be cool if students come to campus, adopt HOPE….and when they become parents they are introducing their children to the framework of HOPE? And when they enter the workforce they are using HOPE? – Lori Clarke, Co-Director, San Diego State University’s Social Policy Institute

SDSU’s call to action to become the first HOPE-Informed university

Lori Clarke, co-director at San Diego State University’s Social Policy Institute (SPI), remembers the feeling of inspiration when she attended a HOPE network community meeting in spring of 2023, where the HOPE National Resource Center’s Director Robert Sege, MD, PhD, spoke to professionals from children and family-serving organizations. At the end of the meeting, Dr. Sege made a call to action. He asked the attendees what they were going to do now that they’d learned about the HOPE framework.

For Clarke, the answer was clear. She wanted to make San Diego State University (SDSU) the first HOPE-Informed University.

“Wouldn’t it be cool if students come to campus, adopt the HOPE framework….and when they become parents they are introducing their children to the framework of HOPE? And when they enter the workforce they are using the HOPE framework?” says Clarke.

Clarke’s enthusiasm is connected to SPI’s vision that everyone across the lifespan is safe, educated, healthy and well, with a sense of belonging, purpose and opportunity to achieve their aspirations. The Institute supports a range of different partners — government, direct service organizations, and the university itself — in thinking through the holistic wellbeing of their constituents. Since the HOPE framework focuses on the needs of a whole person, and the various community and environmental factors that can make a person well, SPI took to it immediately.

Yvonne Epps, SPI project manager and one of the spearheaders of the project, also sees the potential for the HOPE framework’s ripple effect.

“Even though the framework is geared towards early childhood, children, and families,” she says, “we saw that there was opportunity to really expand that to include older adults, to include college students…because everyone deserves to have access to those healthy to those positive experiences.”

Becoming a HOPE-Informed university is new terrain for everyone.

“There’s no playbook for bringing the HOPE framework to a college campus. So we’re just trying to figure it out. That’s … fun and exciting,” says Epps.

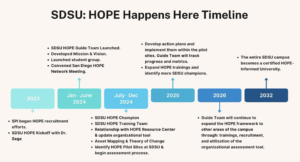

Getting HOPE-certified is certainly one element, but SPI’s vision extends beyond that. They’ve outlined a 10-year plan to integrate the HOPE framework across the university system — academics, student services, personnel — to improve the mental health of its community. Epps says the need for a broad scale intervention is particularly high because of the lingering impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We’re seeing really high rates of students who are experiencing mental health issues and crises … seeing students who aren’t doing as well in their programs as we have seen in years past.” She adds that faculty and staff “are feeling like they have to play multiple roles, not just as teachers but as support for their students as well.”

Integrating HOPE at San Diego State

I think that the HOPE framework really lets us use what students need in all their different identities and kind of unite those needs, under the [Four] Building Blocks [of HOPE]. – Jakob Schmall, Program Coordinator, SPI

Reviewing the offerings

The HOPE framework is centered around the Four Building Blocks of HOPE, which are safe and supportive relationships; safe, stable, and equitable environments; opportunities for social and community engagement; and opportunities for emotional growth. SPI’s first task in integrating the HOPE framework was looking at what resources the university already has, through the lens of these four categories.

SPI defines university resources broadly: They range from standard mental health services to campus cultural events and opportunities for engaging in civic life. They can be identity-specific, like the Pride Center which provides an inclusive and affirming gathering space for individuals of all sexual and gender orientations and their allies. They can be as tangible as a physical building, or as intangible as an online community space.

Using the HOPE framework for asset mapping is like putting on a pair of glasses that allows you to see everything with the question: What Building Block(s) does this resource offer?

The SPI team, along with the support of a “Guide Team” of SDSU students, faculty, and community partners, spent a summer doing macro-level asset mapping and connecting with partners across San Diego who are engaging with the HOPE Framework. Jakob Schmall, SPI program coordinator, says the HOPE framework works for asset mapping because it helps them think about the needs of the various demographics on campus.

“I think that the HOPE framework really lets us use what students need in all their different identities and kind of unite those needs, under the Building Blocks.”

One example of an intersectional identity that asset mapping brought to Epps’ and Schmall’s attention is SDSU students who are also parents.

“There wasn’t anything [on campus] specific for SDSU students who are parents. We do have… the Children’s Center and we also have lactation rooms. But it’d be interesting to explore with [student] parents at SDSU, what else do they need?” Epps says, “Are there certain areas of the Four Building Blocks that we can really build upon to help them feel like they are able to, like really thrive while they’re going to school?”

The HOPE framework in daily life

Now that the first stage of asset mapping is complete, SPI is able to pilot the introduction of new mental health resources at SDSU. This fall, HOPE Champion Jennifer Alcaide will be supporting social work professor Shelly Paule to test out classroom interventions that will cover all Four Building Blocks.

While the full plan is yet to be developed, one example of a HOPE intervention being considered for the classroom is creating time and space for the professor to have conversations with the students that aren’t exclusively about academics. Epps describes it as a “check-in,” something that can be as brief as “How are you doing today? Is there anything that you need for me before class begins?”

The pilot, which will be designed with student input, will include one class that utilizes HOPE interventions and one class, the control, that doesn’t. Surveys will be performed at the beginning and end of the semester.

Schmall says that making professor-student interactions feel more supportive and safe is a “mind shift that has to happen.” Check-ins are a way for professors to acknowledge the range of things that students are dealing with “that might come in between them … being able to complete all their tasks on time.”

Because the mental health needs of the university are so high, SPI feels it’s not realistic to designate supportive relationships only to formal counselors. Epps says that professors and student services staff are often on the front line in interacting with students, and they need to be equipped with tools to provide support.

Epps says SPI will move on to more targeted asset mapping this year, continuing to engage students in the process and honing in on specific colleges and departments within the university, like the School of Social Work, to do more pilots. Schmall says SPI’s guide team also plans to engage with other universities, local schools, and community groups to support them in adopting the HOPE framework.

What does the HOPE framework look like in your work?

Do you have an amazing story to share on how you are using the HOPE framework in your work with children and families? Are you looking to start prompting positive childhood experiences? Reach out to us!